Transcription of the video above

So why can’t you use a guitar tuner on a piano? The problem boils down to the fact that the piano has a lot of real estate, and effectively, the guitar tuner is not listening for the right note. Up here around the middle octave, the tuner will have no trouble assuming you mute the outer strings so that you’re only hearing one string at a time.

A person might reasonably assume that down here tuning an E, the tuner will be listening for an E, but that’s not the case. A vibrating string produces more than one pitch. That B you heard is here, and it’s the sixth partial.

In a theoretical model, those notes would line up, but this isn’t a theoretical instrument. These strings are thickly wound, they’re heavy, and they’re loose, and they operate more like a pipe than they do like a two-dimensional string. The partials go progressively sharp in relation to the fundamental tone of the string.

Effectively, this note is out of tune with itself. The word is “inharmonicity.” Band name called it. To make sure that this note is in tune with this one, or with this B, we need to progressively tune them flat.

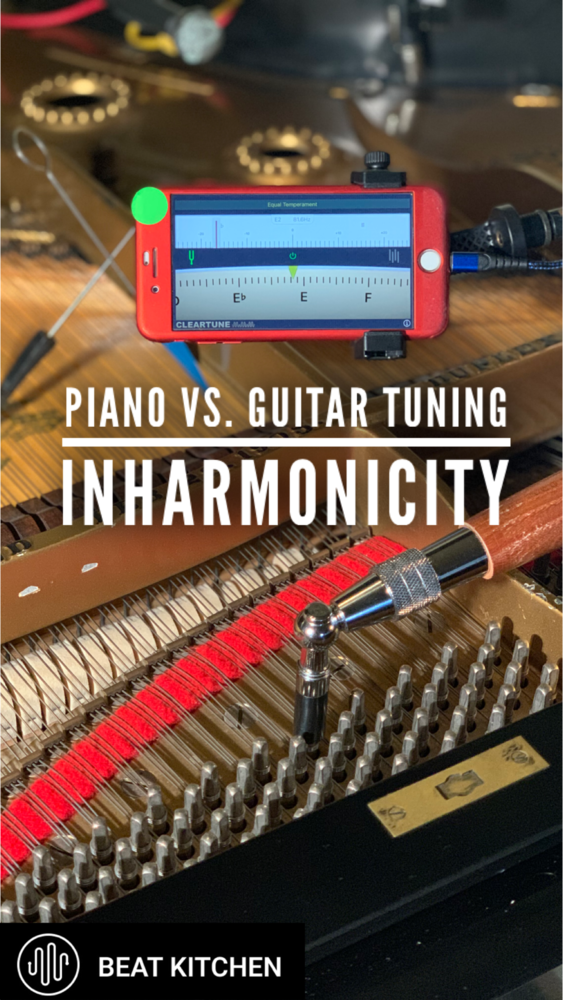

It’s called stretching the piano, and when we tune, we’re not actually listening for the E. We’re listening for the partial to make sure it matches, and the guitar tuner just can’t handle that. Here’s how it looks when you compare the two.

Tune lab shows it dead on, guitar tuner shows it flat. If you learn something like this post, share it with somebody who belongs in a Beat Kitchen class.