Transcription of the video above

Within the lexicon of recording and mixing, the concepts of phase and polarity are similar enough. They can sometimes be used interchangeably, but they’re different. A microphone is sensitive to air pressure, and the push-pull nature of those changes in a periodic waveform can be seen like a tug of war between positive and negative values.

If one side is pushing and the other side is pulling, we move the needle. But if both sides push or pull with equal force, there is no change. This is most easily seen if we simply invert the polarity of a copy of the waveform.

You could do this by swapping out the black and red leads of a speaker. It’s akin to turning a battery upside down. Positive goes to negative, negative goes to positive, and the result in every case is that you will get full cancellation.

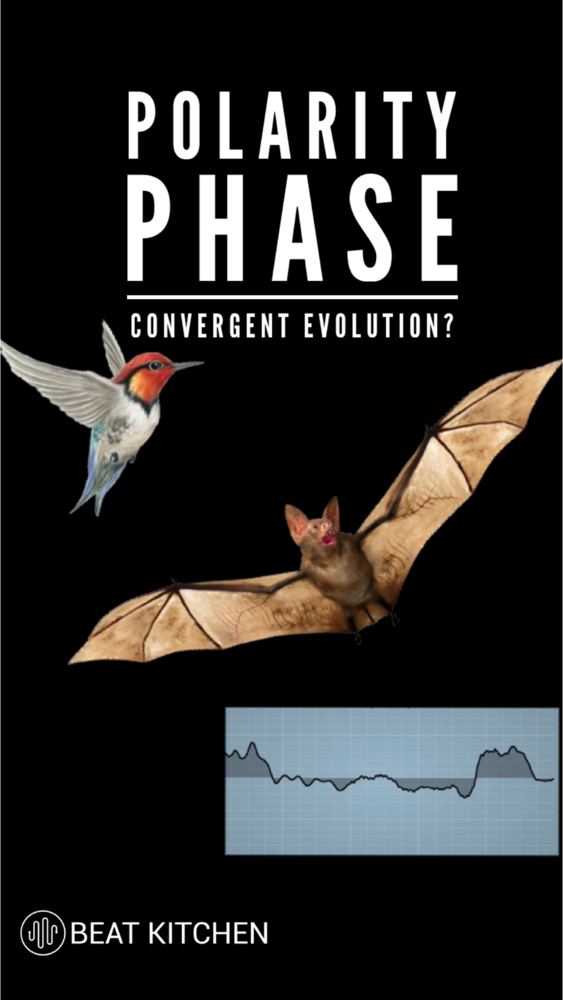

The confusing bit is when we consider what is distinctly different about phase. Over a static, unchanging signal like that of a synthesizer oscillator, if we apply a small delay, we might end up with a case of convergent evolution, where the result is the same. But out in the wild, sound doesn’t work that way.

The pitch, timbre, and amplitude tends to evolve and change. A signal’s fingerprint a few milliseconds downstream is unlikely to be identical. What happens in these cases is that depending on the tiny delay, which we’re calling phase shift, some frequencies will cancel, but others will build up.

This can result in an elaborate comb-shaped pattern of constructive and destructive interference. So phase and polarity, two different concepts, sometimes with the same result. And if someone who wants to spend a little more time on this in a Beat Kitchen class, please share this post.